The suicide of a pensioner outside the Greek parliament, the latest in a series, sums up the mood of a population confronted with the steady erosion of its rights. Victor Tsilonis wonders whether tomorrow will be just another day in Greece’s “predestined” future.

“What if there was no tomorrow? There wasn’t one today!”

In the 1993 film Groundhog Day, Bill Murray finds himself in an extremely odd situation. Like every year, he is in the small American town of Punxsutawney to report on an event anxiously awaited by the locals: the emergence of the groundhog from its wooden hut to “forecast” whether the winter will be particularly long and harsh, or whether, against all odds, spring will come early. At first, everything seems to be “business as usual”, however he soon realises not only that an unexpected blizzard means that he is secluded in this small town, but also – and more importantly – that his coverage of the groundhog’s forecast will be incessantly repeated, day in, day out.

Nineteen years later, in April 2012, two-and-a-half years into the economic crisis that first “accidentally” hit Greece at the end of 2009, following the financial turmoil sparked off by the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in the US and the mysterious series of “actions and inactions” of the government of George Papandreou III (with the inevitable consequences this had on the lives of the Greek citizens), some people are reminded of exactly that movie.

Like in the film, the weather also plays a role: a slow but unrelenting rain poured down throughout the first week of April, the gloom, unusual for Greek standards, compounding people’s utterly downcast and pessimistic sentiments about their future wellbeing and their mortgaged freedom and independence.

Thursday afternoon was always market day on Mitropoleos street in Thessaloniki (the second largest Greek city), but on the day I was there shoppers were few and far between; in fact, I was dumbfounded to count 14 shops in a row without a single customer. Before the crisis began, Thessaloniki had almost 1.5 million residents, however at the current rate of exodus it will have less than 500,000 in five years time. So it was hardly a surprise to see only a handful of people on what used to be one of the city’s main commercial streets.

Still, prices in Greece remain amazingly high and the Greek market continues to be among the most expensive in Europe, notwithstanding the fact that salaries and other “expenses” (monthly allowances, benefits, etc.) have sharply fallen by well over 40 per cent; in fact the minimum wage has gone down to 490 euros per month, thus turning back the clock to 2005. On top of that, unemployment has skyrocketed, officially surpassing the record of 20 per cent, though unofficially (i.e. realistically) it is at least 30 per cent. Youth unemployment is currently well over 60 per cent, although official statistics acknowledge a more modest rate of 48.1 per cent.

Furthermore, unconstitutional enactments of law continue in all fields. It cannot be overstated that, for quite some time, Greeks have been seeing their hard fought rights vanishing into thin air, and that this trend will continue in the future. To name but one recent example, a new law regarding the “Fair Trial and the Acceleration of Justice” requires victims of crime (such as threat to life, verbal abuse, defamation, illegal damage of property, simple bodily harm) to pay 168 euros in order to file an official complaint, without which their case will not be examined by the police and judicial authorities!

Every day seems to bring another suicide, adding to the 1750 suicides that have taken place in the last two years throughout the country. And while many remain concealed by the ashamed relatives of the victim or, more often, deliberately omitted from the targeted information provided by the public media, many others cannot but find their humble way in the storylines. Arguably the first was Leonidas Margiolis, owner of the acclaimed “Seven Seas” restaurant in Kalapothaki, the pedestrian street of Thessaloniki, who quietly fell from his balcony one night after racking up huge debts to loan sharks. Then it was Christos Charbatsis, a well-known theatre director in Greece, who chose not to leave our world without material possessions, choosing a Pharaonic death by driving his favourite car into the cold waters of Piraeus harbour.

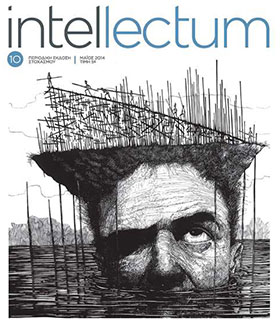

Most recently it was Dimitris Christoulas, a 77-year old retired pharmacist who, more glamorously still, opted to kill himself with a pistol in front of the Greek Parliament. In his final note he did not mince his words, comparing the current leadership with the collaborationist government of Georgios Tsolakoglou and blaming it for “nullifying” any chance for his “survival”. “I can find no other solution than a dignified end, before I start scavenging through waste bins for my food,” he wrote, ending by sounding a hopeful note: “I believe that the young people with no future will one day take up arms and hang the traitors of this country on Syntagma square, just like the Italians did to Mussolini in 1945.”

The weather has since returned to its sunny glory days, at least until midday, causing optimism to return to some. What’s more, elections are near and the hope remains that people will at last repudiate the propaganda of “inevitability” propagated by the mass media, and that a real change will be brought to Greece’s predestined and catastrophic future, both in constitutional, labour and human rights as well as the economy itself.

However, this will be neither easy nor foreseeable; most probably, change will happen unexpectedly, when almost everybody has lost hope. Perhaps it already started the moment a 77-year old former pharmacist decided to commit suicide on Syntagma Square.

Perhaps.